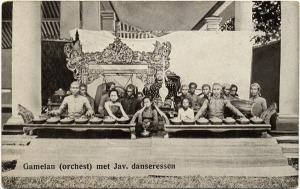

As many of you probably know, the term “gamelan” refers to an entire ensemble of instruments, as well as the music played by said ensemble. A gamelan consists of bronze gongs of different sizes and bronze keyed instruments that look something like a xylophone. Percussion, fiddle, flute and voice may also be included. Each gamelan is a unique set of instruments with it’s own sound, tuning and character. Instruments from one gamelan cannot be interchanged with another ensemble.

Most Balinese, Javanese and Sundanese gamelan are tuned to one of two main scale systems, pelog and slendro. Pelog has seven pitches and is reminiscent of a Western major scale, although notes don’t exactly match up. Slendro (or salendro in Sundanese) is a five note scale in which all the notes are basically equidistant, something not found in western music. It’s important to remember that each gamelan has a unique version of these tuning systems, not to mention the range in which it’s tuned.

The music played by a gamelan is built in layers. Generally speaking, the higher pitched instruments play a denser more elaborate melody, more notes per minute. Lower pitched instruments play versions of the melody that are simpler and sparse. The important thing is that all the instruments land on certain important notes together. This concept of simultaneous variation is common throughout Southeast Asia. Check out the Vietnamese Vong Co recordings on this site for some other striking examples of simultaneous variation. Gamelan music uses interlocking patterns to create a temporal structure. The combination is termed “polyphonic stratification.” An academic term that creates a nice mental picture. As a student at the University of Michigan, 20 years ago, I played in the Javanese gamelan ensemble and my favorite moment was always when the lowest (and largest) gong would sound at the endpoint of each cycle. The effect was monumental as all the instruments concluded their melody and the low gong rippled throughout the room. You feel it more than hear it.

Gamelan music is hundred’s of years old, but the first recording label to venture to Indonesia, which was then called the Dutch East Indies and controlled by the Dutch, was the German label Beka, in 1905. They were followed a year or two later by Odeon. The Gramophone Company lagged behind in entering the Indonesian market. In fact, Odeon had come to dominate the Indonesian market to such an extent that in 1909 Frederick Gaisberg complained, “The business in Java for the Odeon company has been wonderful for the last two years, they being the only company in the field. The Odeon Company, during the last two years, have made two recording trips to Java, and are now starting on a third.” (Paul Vernon, Odeon Records; Their Ethnic Output).

In 1911 Beka was absorbed by Odeon and around the time of this recording, in 1931, both labels were part of the huge EMI merger.

Here’s a piece in the pathet sanga. Pathet is the Indonesian version or modes, raga, maqam, etc. Sanga is one of the three central Javanese modes in slendro. I believe this piece is from Surabaya, in Eastern Java, so the version of pathet differs from the Central Javanese. It’s sung by the pasinden (female singer) M.A Soetinah.

Gamelan records are extremely hard to come by, highly sought after and usually pretty beat up. I’ll post a few of my more listenable records, but you should also check out 78 collector Mike Robertson’s youtube page. Mike has a fantastic collection of gamelan records (and more) which you can hear on youtube.

Somehow, they seem to fall right out of the sky and into Mike’s lap!

One thing that I love about Southeast Asian music is the sense of multiple melodies swirling around each other, weaving in and out, yet always seeming to end up in the right place. This is especially true of gambang kromong.

Gambang kromong is a vernacular music from the outskirts of Jakarta. It is the music of the Betawi, long time inhabitants of the Jakarta area of Java, as well as the Peranakan, people who are a mix of Chinese and Indonesian. The music is often performed at weddings or in musical theater.

The ensemble consists of gambang, an 18 key xylophone and the kromong, a small set of kettle gongs. Other instruments often included are a 2 string fiddle (tehyan) similar to the erhu, suling (flute), an array of percussion instruments and anything from western brass to electric guitar (see Folkway’s Music of Indonesia vol. 3).

Irama was Indonesia’s first independent record label, started in 1954 by Suyoso Karsono. Irama released a wide variety of traditional and popular music.

Here’s a fantastic Tembang Sunda recording from 1935. The featured instruments are the zither called kacapi and suling, a bamboo flute. The singer, Nji Raden Hadji Djoeleha, embodies the old style of singing, higher pitched and nasal. The older style also uses different ornamentation, for example, jenghak, the use of the break between chest and head voice which can be heard on this recording.

Tembang Sunda was originally known as Cianjuran, from Cianjur, the court city in west Java. It’s a form of poetic singing that emerged out of several other Sundanese genres, especially pantun, in the early 19th century and was promoted and enjoyed by the aristocracy. The songs glorify Pajajaran, the legendary Hindu kingdom of the 14th and 15th centuries.

The other side of this record can be heard on Ian Nagoski’s “Black Mirror“, released by Dust-to-Digital.

Upit Sarimanah (1928 – 1992) was an extremely popular singer from Sunda, the mountainous western region of Java. She was a sinden, the female singer in the traditional puppet plays known as wayang golek. Her first recordings were made in the 1950s and she was loved for her warm, deep chest voice as opposed to the high, nasal head voice of her main contemporary Titim Fatimah. Fatimah’s voice was considered rougher and unrefined while Upit’s style was more modern and embraced by the urbane and sophisticated urban population. Andrew Weintraub writes that one musician told him “America had Elvis, Indonesia had Upit.” (The Crisis of the Sinden, p. 67)

She was a versatile singer, recording in everything from pop styles to keroncong to traditional gamelan. Upit first recorded 78s for the Nusantara label as well as the short lived Putri label, both offshoots of Radio Republik Indonesia (RRI). She went on to record many lps for Indonesian labels such as Mutiara, Canary, Evergreen, Lokananta and others.

Mangle is the Sundanese name of the jasmine flower worn as a decoration in the hair of a bride during wedding ceremonies, but it also has a larger symbolic meaning of “sacred beauty.” The song was composed by Mang Koko Koswara (pictured below), a popular composer of the 1950s known for modernizing Sundanese music.

Here are the lyrics in Sundanese if you’d like to sing along.

MANGLE

Ampuh lungguh someah

tara rucah awuntah

Resep cicing di imah

Babalik pikir

Ka bioskop bet ngampleng

Di arisan ge suwung

Ka pakgade ge lebeng

Babalik pikir

Di Tepas teu tembong

Bumi siga kosong

Horeng susulumputan

Leuh sieun rekening

Ngadadak bet lungguh

Ulat ampuh timpuh

Pajar babalik pikir

Horeng kantongna kosong

Kurang kerung ngadilak

Gawe nyeuseul ngawakwak

Ka pagawe sesentak

Bapa kapala

Agar kerja dinamis

Inspirasi yang praktis

Kudu nyanding nu geulis

Keur maen mata

This post is a bit of an update to my earlier post from Inner Mongolia.

Hisao Tanabe, a Japanese musicologist, supervised the release of three collections of Asian music on 78 rpm record. The first was called Toa no ongaku (Music of East Asia) released in 1941 Nippon Columbia.

The second set, Nanpo no Ongaku (Music of the South) was relased in 1942 also by Nippon Columbia. It was a set of six 78s that included music from around Southeast Asia. I’ve never seen any copies of either of these two collections. Give a shout if you have them!

In the same month, another Tanabe collection was released by Nippon Victor called Daitoa Ongaku Shusei (A Greater East Asian Music Compilation.) This was an epic set of thirty-six 78 rpm records, divided by region into twelve albums of three records each.

I have not managed to determine all the regions that are represented in this set, so far I have found two different albums from China, one from India and one from Indonesia, plus one of the three records from the Inner Mongolia album. The cover of the Indonesian album, below, shows more than 12 regions, so it’s not clear if all these places are represented on the set.

Advertisements for the set included the excellent line “An anthology of the musics of Greater Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere prepared under the supervision of the most authoritative scholarly society.”

Tanabe theorized that all Asian musics had a common basis and that somehow Japan represented the purist expression, or culmination of “Asian music.” This philosophy meshed nicely with Japan’s imperialistic intentions. The sets he compiled were a kind of response to the famous Music of the Orient by pioneering ethnomusicologist Erich von Hornbostel, a set of twenty-four 78s released in 1931. Tanabe felt that Music of the Orient was too steeped in exoticism, yet his own theories are rife with racial stereotypes and musings about some intangible ancient “Asianess.” What makes matters stranger is that Tanabe went on to lift selections from Hornbostel’s collection and reissue them in his own! All the records on Tanabe’s sets were from previous releases.

Hornbostel’s collection was really the first compilation of world music 78s, the prototype for Secret Museum of Mankind, Excavated Shellac, Haji Maji and others. It’s popularity is evidenced by the fact that it was re-issued by Decca and again by the English Parlophone label. Tanabe’s collections have never been fully reissued and his notes have yet to be translated into english. At least one side, from Inner Mongolia, was included on the Secret Museum of Mankind Central Asia cd.

I don’t think anyone has determined where all the Tanabe records were originally issued. I suspect this one was from Beka. It features the Sundanese zither called kacapi, performing the epic poetry known as Tembang Sunda.

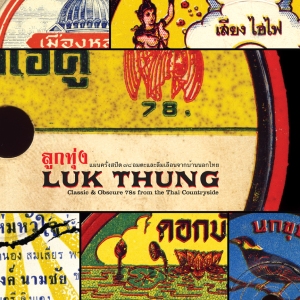

I’m happy to announce Haji Maji’s first official release:

LUK THUNG, Classic & Obscure 78s from the Thai Countryside

UPDATE: This appears to be out of print. There may still be some shops that have copies left or you can try good old Ebay.

I’ve collaborated with Peter Doolan, of the great Thai cassette blog monrakplengthai, on an album of 14 early Luk Thung 78s from Thailand, published by the Grammy Award-winning label Dust-to-Digital on their vinyl imprint Parlortone.

That’s right, VINYL!

No turntable? Don’t worry, it’s available for download on iTunes and Amazon.

It was compiled by me from my collection. Peter researched and wrote the notes while living in Bangkok last year.

The album explores similar ground as Sublime Frequencies’ “Thai Pop Spectacular”, “Thai Beat A Go-Go” from Subliminal Sounds and Soundways’ “Sound of Siam”, but with a focus on the earlier, down-home roots style instead of the rock and pop influenced material found on these other reissues. The garage band/proto-Thai rock stuff is cool, but here at Haji Maji our interest tends toward the raw, rural and traditional sounds.

Here’s a sample track from the album:

Ruedu Haeng Khwam Rak (Season of Love) by Phloen Phromdaen

Included in the album is a 6 page, full-color insert with detailed notes and images of the various record labels.

From the notes:

“Luk Thung is known to many as Thailand’s “Country Music”; it’s a vibrant and syncretic genre of pop song which aims to give voice to a disenfranchised rural population… farmers and migrant workers, as well as gamblers, drug addicts, outlaws and other marginal figures…the strain of Luk Thung captured on this album is one marked by a conscious move away from Western influence and an embrace of traditional musics…”

Special thanks to Jon Ward, Michael Graves, Debbie Berne, Rob Millis and the Dust-to-Digital crew.

Enjoy!

Miss Riboet’s popularity continued to grow, both on stage and on record. In 1929, the Dardanella theater troupe emerged and soon became rivals with Miss Riboet’s Orion troupe. Dardanella had several big stars in the troupe and in 1931 found themselves in court because one of their stars was also using the name “Miss Riboet.” Dardanella lost the case and their imitator had to switch to “Miss Riboet II.” I’m not sure how many songs she recorded, I’ve only seen one. Here’s Miss Riboet II pictured with another Dardanella star, Miss Dja:

Since this second post about Miss Riboet is about the second Miss Riboet, here’s the second side of the Miss Riboet record.

Thanks to Matthew Isaac Cohen for noticing that I had mistaken Miss Riboet II for the real thing in my previous post.

Miss Riboet was the first huge star of recording in Indonesia and the Malay peninsula. She was the lead actress of the Orion theatrical company, a tooneel troupe which was founded in 1925 in Batavia (Jakarta). In fact, she was so popular that by the time recording engineer Max Birkhahan made this recording in 1926 she already had her own series of “Miss Riboet Records.”

The label declares this a “Stamboel” recording, a western influenced genre of song that evolved out of the Indonesian theater known as “komedie stamboel.”

Komedie stamboel was a form of musical theater that started in the city of Surabaya in 1891 and quickly became a craze throughout Indonesia. At first, it featured plays of arabesque fantasy (Stamboel = Istanbul), mainly tales from the Arabian Nights, with Ali Baba being a favorite standard. The plays were sung and included musical numbers as in a western musical, using mostly western instruments. They were also influenced by Parsi theater. There is an excellent book by Matthew Isaac Cohen that gives an extremely detailed account of the origin of Komedie Stamboel.

By the mid-20s, when Miss Riboet began recording, komedie stamboel had already given way to the Malay theatrical form called bangsawan, and eventually tooneel, a more realistic form.

Apparently komedie stamboel had developed a somewhat unsavory reputation that led in part to it’s demise, some troupe leaders were accused of doubling as pimps for the actresses!

The music was often labeled as “Stamboel” on record, regardless of whether it was a stamboel, fox trot, tango, krontjong or traditional piece, such as this Javanese poetical form called Pankgkur.

Filed under: Announcements

Dear Haji Maji Readers,

The new year began with the death of my computer. fun.

As we move into year four of Haji Maji, I’ve decided to do a little blog fundraising. If you’ve been enjoying the rare, un-reissued recordings over the last few years, please consider supporting Haji Maji by throwing five bucks into the tip jar via the “donate” button on the left. You can rest assured that it will go back into the blog, in the form of records, bandwidth, images, etc.

There’s plenty more good stuff lined up, so stay tuned!

cheers,

HM

Here’s another Pagoda recorded in Singapore, this one in 1938. It features traditional Chinese wedding music played by a seroni ensemble. The typical ensemble consists of seroni (a shwam-like oboe known as suona in China), swilin (bamboo flute) and percussion; a small drum, cymbals and gong. Usually this type of music is used to accompany the bride while she is carried in a sedan and throughout other parts of the wedding. The piece heard on this record is labeled “Siew-Tow”, the most important part of the ceremony when the vows are taken.

A seroni ensemble is also used for funerals and other rituals.

Immigrants from southern China began moving to Malaysia and Indonesia as early as the 15th century. The British later encouraged Chinese immigration to the Straights Settlements in the the 19th and 20th centuries. Chinese, speaking several different dialects, quickly established themselves as traders throughout the region, as in other parts of Southeast Asia.

The label is hard to read, but it says:

Seroni

lagu Siew-Tow